Farroshar Language

Of the Origin of the Farroshar

Far beyond the mountains and the shore’s outermost stretches, past the hills and the grasslands and where the jungle greets the sand… a people called the Farroshar wander the desert endlessly. Their cities are sacked, their books burned, and their people driven from safety… but still they travel with all that remains: their language. Few foreigners speak this tongue, and far less even among their own kind can write its script. With song and speech, the Farroshar persist into foreign lands—trading, spreading culture, and seeking, seeking, forever seeking the home they lost.

Those who have crossed paths with them know only two of their words: farosh—burnt—and sharnah—faces, appearances. Outsiders may think them scorched by the sun’s rays… but to the Farroshar, it’s a badge of triumph over the land’s heat and fire they endure.

Of Farroshar Consonants

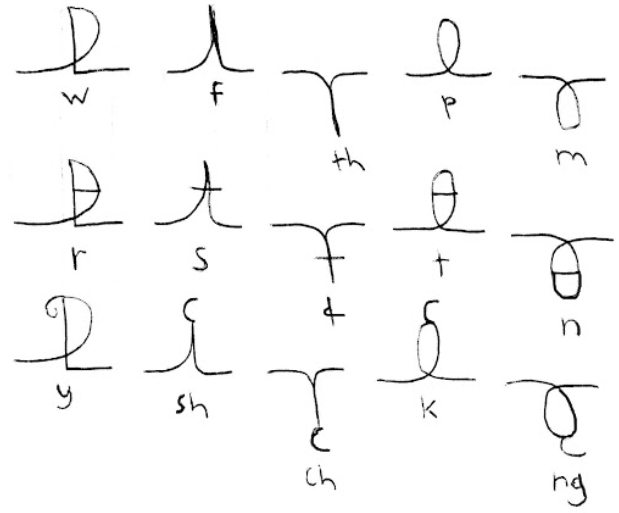

The Farroshar alphabet’s cursive script is represented by five main symbols indicating a consonant’s manner of articulation (approximant, turbulent fricative, non-turbulent fricative, plosive, and nasal) that are each modified by two different types of lines to signify the place of articulation (alveolar or posterior to replace the default symbol for frontal).

An approximant is a consonant sound made by bringing the articulators close together without letting them touch or produce friction, such as w, r, l, and y. A nasal consonant is a gentle sound made by directing airflow through the nose rather than out the mouth, like n, m, or ng. Approximants and nasals are described as gentle, airy sounds—like a cool breeze scaling the dunes of the Farroshar deserts. A plosive consonant involves a powerful, explosive release of the articulators—like p, b, t, d, k, and g—to form a loud sound akin to the crack of exploding gunpowder or the thump of an elephant’s footfall on the desert floor.

Six fricative consonants are present in Farroshar, each of which is produced by forcing air through a narrow gap between the articulators to create friction. Fricatives are turbulent if they form a hissing, sibilant sound with high velocity—like s, sh, and /ɸ/—noises which the Farroshar liken to the hiss of a rattlesnake or a puff of air quelling a candle asleep. Essentially, the turbulence category is similar to sibilance or stridence though extended to include a broader range of fricatives. If the fricative’s articulators are too obstructive and awkward to meet these standards, the fricatives are non-turbulent—like the grind of two stones against one another.

The absence of eight voiced obstruents (plosives & fricatives) a linguist might expect—/β/, /b/, /ð/, /d/, /z/, /g/, /ʒ/, and /ɣ/—originates in the harsh, desert-like territory of the Farroshar and the weakening their vocal chords have suffered over millenia. This imbues each consonant with a voiceless, whispery quality adding to the mystique of the language. Smaller dialects of Farroshar, especially those spoken in permanent settlements and more humid environments, may retain some voiced qualities as allophones—slight variations of a sound that don’t change the word’s meaning—especially when they’re surrounded by vowels on both sides during a phenomenon known as intervocalic voicing. This can confuse foreigners and often result in various transcription styles, though many prefer to stick with the standard “no voiced obstruents” rule which adds a layer of uniqueness to the language.

Of Triconsonantal Roots

Farroshar’s entire vocabulary is based on triconsonantal roots, a feature in many Semitic languages like Arabic and Hebrew. This system involves establishing a sequence of three consonants in a row before tying a certain meaning to this root. In Semitic languages, these roots are modified into words using binyanim—vowels used to “fill in the blanks” and add meaning. Farroshar’s roots are modified, not by vowels, but by changing its consonants instead. Essentially, consonants are a set of mudbricks bound together by the mortar of vowels—and when one brick is swapped for another in a certain way, it’s enough to tell the observer why and how this mudbrick wall has adapted before the onset of a new climate.

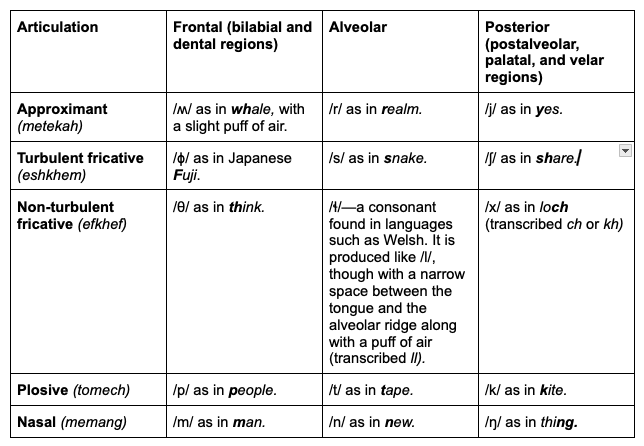

One root undergoes twenty-four separate modifications. A modification will be defined here as a way of changing one individual letter in order to change its meaning. Modifications are the product of two main factors: articulation and ordinality. Articulation includes the three places (frontal, alveolar, posterior) and five manners (approximant, turbulent fricative, non-turbulent fricative, plosive, nasal) of articulation. Each of the eight articulatory changes bears more of a core meaning than ordinality. These include adjectives, noun forms, and verb conjugations. Ordinality, on the other hand, is which consonant—of the three present in a root—will be changed, determining more specific details such as a verb conjugation’s future, present and past tense variations. Therefore, a complete list of twenty-four modifications stems from the formula 3 (ordinality) x 8 (articulation).

During modification, each consonant can be changed to its equivalent partner in either place or manner of articulation. For example, T is alveolar (place) and plosive (manner). T’s partner in the turbulent fricative class (manner) is S, and P is the partner for frontal (place). For example, the root F-R-K (meaning “fire”) can form fasok (it burns) because S is both the word’s second consonant (associated with present tense) and R’s turbulent fricative equivalent (associated with simple verbs, like eat instead of eating or eaten). To make fasok past tense, simply modify the third consonant K instead to form farosh (it burned), or efarok for “it will burn”. Modification begins with first-consonant approximants before moving on to the second and third consonants, proceeding then to move down the list of articulatory classes and repeating the C1, C2, C3 pattern for each. Check out the table below for a more visual explanation.

Example

F-R-K 🔥

Wharok - will be burning. Farok - is burning. Faroyo - was burning.

Efarok - will burn. Fasok - burns. Farosh - burned.

Tharok - will have burnt. Fallok - has burnt. Faroch - had burnt.

Parok - if it’s going to burn. Fatok - if it burns. Faroko - if it burned.

Marok - fiery. Fanok - not fiery, fireless. Farong - very fiery, conflagratory.

Ifarok - an individual fire. Fawhok - fire as a collective aspect. Farop - fires.

Sarok - burner. Fareek - heat, hotness. Farot - burners.

Sharok - of a fire or burner. Fayok - of heat, of hotness. Farokih - of fires or burners.

Of the Pronunciation and Orthography of Vowels

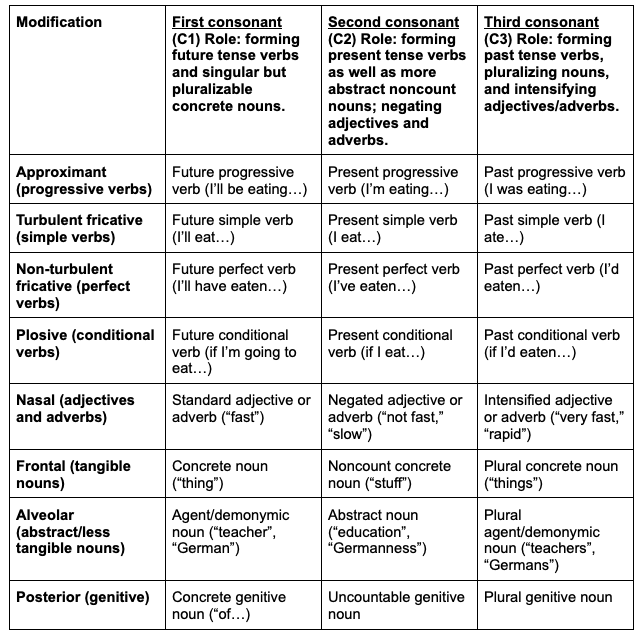

The Farroshar alphabet is an abjad: its letters are strictly consonants, much like the ancient scripts of many Semitic languages. Vowels (metat, singular netak) exist instead as four main, distinct diacritic symbols placed above/below consonants to represent short vowels, each of which can be lengthened/diphthongized by writing macrons (horizontal line marks) on the consonant preceding the long vowel. Being quickly written and relatively unimportant to the language, vowels have quite flexible pronunciations which may vary by dialect.

If two vowels are ever written side-by-side, an allophonic glottal stop (think: the tt in button or the space between uh and oh) always occurs in speech. In Latinized transcription, the apostrophe signifies a glottal stop. In Farroshar, however, a glottal stop is not represented as a letter due to its diphthongs being represented by individual diacritics rather than a digraph like English ee, ai or oa. Glottal stops thus can never occur directly before or after consonants.

Of Sequence Repetition

Vowels are added to a word if its triconsonantal sequence repeats one that has already appeared. When a sequence is repeated, either the modified consonant is assigned an existing, neighboring vowel or given a new vowel based on the consonant’s details. Both of these have the purpose of forming a new, distinctly-spelled derivative so that no words may be confused with one another based on spelling or pronunciation. This is especially convenient for Farroshar’s triconsonantal root system, which can cause a sequence to be repeated a frustrating amount of times during modification.

Each articulatory factor bears its own assigned vowel in anticipation of sequence repetition, as is shown on the table above. If the repeated sequence contains three vowels—by far the easiest scenario—the ordinality of the vowels will always correspond to the ordinality of the consonants. If it contains more or less than three syllables, then the added/changed vowels…

Precede the modified first consonant.

Follow the modified third consonant.

Either precede or follow the second consonant, depending on which location ensures the most clarity and euphony.

For example, farok (is burning) becomes efarok (will burn) on its future simple conjugation repeat for F, because /ɛ/ corresponds to turbulent-fricative modifications. /ɛ/ goes before F, the consonant being modified and whose ordinality is 1. Remember, the repetition of one sequence is not what determines how it’ll be distinguished; it’s whether or not the changed consonant in this repeated sequence matches a previous modification. Always pay attention to the modified consonant, as this will pinpoint both the quality and location of the added vowel.

Of Euphonious Vowel Insertions

Vowels can also be inserted within a consonant cluster if it blends together two identical letters or a pair considered “ungraceful” by Farroshar standards. For example, if we wanted to make the root shartah (meaning face or appearance) into a past progressive verb (resulting in Š-R-R), we would insert the word’s previous vowel /ɔ/ between the double R to avoid repeating two consonants in a row. Similarly, the letters W or Y—approximants that just beg to be followed by a vowel—must have their wishes fulfilled, borrowing the word’s previous vowel.

In summary, vowels act not only as Farroshar sounds but as sequence distinguishers, backup grammatical affixes, and tools for preserving the bright spark of phonetic euphony in a vast abyss of harsh consonant clusters.

Fun activity👋

Create your own words! Pick three consonants, give the trio a meaning, and add whichever vowels you wish. You could even base a root off your own name! After you’ve established the root’s key features, form twenty-four or more words using the rules and tables above. If you’re puzzled by the whole “sequence distinguishment” bit, I’d suggest you choose three vowels for a clear relationship to the consonants. Bust out some words!

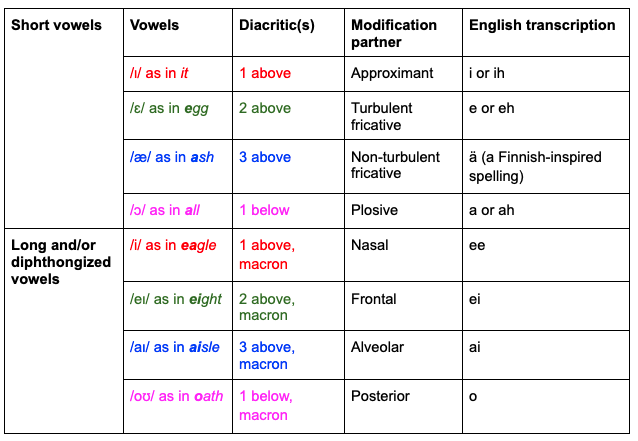

Of Loanword Transcription

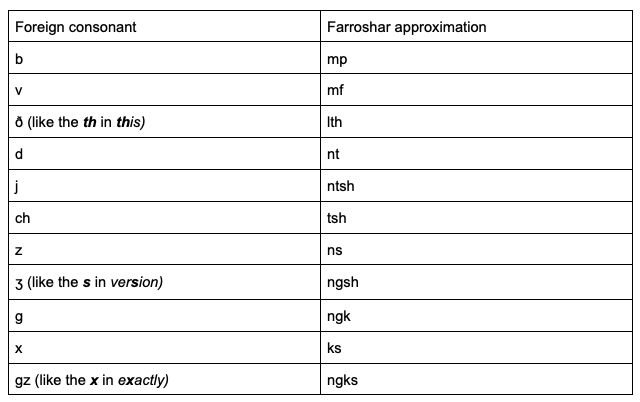

Farroshar has a particular set of rules when transcribing loanwords from other languages into its own script. Check out the table below to see how foreign consonants are spelled out using Farroshar’s alphabet, inspired by Greek transcription styles.

Roots

M-T-K (to fill, complete)

Whetakah - will be filling/completing. Merakah - is filling/completing. Metayah - was filling/completing.

Fetakah - will fill/complete. Mesakah - fills, completes. Metashah - filled, completed.

Thetakah - will have filled/completed. Mellakah - has filled/completed. Metachah - had filled/completed.

Metakah - if (it) will fill/complete. Menakah - if (it) fills/completes. Metangah - if (it) filled/completed.

Petakah - complete. Metekah - incomplete, approximant. Metakeh - fully complete, overflowing.

Mitakah - any form of filling. Mepak - filling, mortar. Metap - multiple different types of filling.

Netak - a vowel, which fills the gaps between consonants. Metäkah - fullness, completion. Metatah - vowels.

Ngetakah - of a type of filling, or of a vowel. Mekakah - of filling, mortar, fullness, or completion. Metakä - of many types of filling or vowels.

N-M-Ŋ (gentle, to touch gently)

Remang - will be touching gently. Newang - is touching gently. Nemaya - touched gently.

Semang - will touch gently. Nefang - touches gently. Nemash - touched gently.

Llemang - will have touched gently. Nethang - has touched gently. Nemach - had touched gently.

Temang - if (it) will touch gently. Nepang - if (it) touches gently. Nemak - if (it) touched gently.

Nemang - gentle, or nasal. Nemeng - rough, harsh. Nemangeh - immensely gentle.

Memang - a gentle/nasal consonant. Nemäng - nasal tissue. Nemam - nasal consonants.

Nemangah - a gentle person. Nenang - gentleness. Neman - gentle people.

Ngemang - of a nasal consonant or gentle person. Nengang - of nasal tissue or gentleness. Nemangee - of nasal consonants or gentle people.

Ainemang - the nose. Menang - nasality. Meman - noses.

Omemang - a synonym for nasal. Momang - non-nasal, oral. Memango - hypernasal.

Š-X-F (friction)

Eyekhef - will be producing friction. Eshyef - is producing friction. Eshkheweh - was producing friction.

Eshkhef - will produce friction. Esheshef - produces friction. Eshkhefeh - produced friction.

Ekhekhef - will have produced friction. Eshkhäf - has produced friction. Eshkhell - had produced friction.

Ekchef - if (it) will produce friction. Eshkef - if (it) produced friction. Eshkhep - if it produced friction.

Engkhef - frictional, fricative. Eshngef - non-frictional. Eshkhem - very fricative, turbulent.

Efkhef - a fricative. Eshthef - the sound of friction. Eshkheth - fricatives.

Eskhef - an object, or articulator, that produces friction. Eshlef - friction. Eshkhess - plural of eskhef.

Aishkhef - of a fricative or eskhef. Eshkhaif - of friction or the sound of friction. Eshkhesh - of fricatives or eshkhess.

P-M-X (explosion)

Whomech - will be exploding. Powhech - is exploding. Pomeyeh - was exploding.

Fomech - will explode. Pofech - explodes. Pomesh - exploded.

Thomech - will have exploded. Pothech - has exploded. Pomechä - had exploded.

Apomech - if (it)’s going to explode. Popech - if (it) explodes. Pomek - if (it) exploded.

Momech - explosive, plosive. Pomeech - non-plosive. Pomeng - highly explosive.

Eipomech - an explosion. Pomeich - gunpowder. Pometh - explosions.

Tomech - an explosive device, or a plosive consonant. Ponech - explosivity. Pomell - explosive devices, or plosive consonants.

Komech - of an explosion, explosive device, or plosive consonant. Pongech - of gunpowder or explosivity. Pomecho - of explosions, explosive devices, or plosive consonants.

Glossary

🔊 Phonetic basics:

👂Phoneme - the smallest perceptible unit of spoken word; a sound. Think: bat vs pat.

🔇 Allophone - a variation of a phoneme that can’t change the meaning of a word. For example, apple and animal have different first allophones despite a shared first phoneme.

🙊 Voiced and voiceless - a voiced consonant involves vibration of the vocal chords, while a voiceless consonant does not. Every fricative, plosive and affricate has a voiced or voiceless equivalent, such as the voiced b and voiceless p.

2️⃣ Diphthong (verb: diphthongize) - when two vowels blend to make a new sound.

🆖 Digraph - when a pair of two letters—either vowels or consonants—make one sound.

🗣️ How sounds are made:

👅 Articulator - one of the mouth’s features capable of articulating (producing) sounds.

📌 Place of articulation - the region of the mouth in which a particular sound is articulated, including bilabial, ambidental, alveolar, and retro-alveolar.

👄 Bilabial - a consonant produced using both lips. Think: b, p, m, w.

🦷 Dental - a produced with the tongue touching the upper teeth. Think: th.

🧱 Alveolar - a consonant produced on the ridge behind the upper teeth. Think: d, t, z, s.

🔙 Posterior - not a standard IPA term, but used in this context to mean “a consonant produced behind the alveolar ridge”. Think: sh, g, k.

⚙️ Manner of articulation - the fashion in which a sound is articulated, including nasal, “incomplete”, fricative, plosive, and affricate.

😤 Nasal - a consonant produced by directing airflow through the nose rather than out the mouth. Think: m, n, ng.

🤏 Approximant - a consonant where the articulators are brought together without creating friction. Think: w, r, l, y.

🌬️ Fricative - a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow gap between the articulators, creating friction. Think: v, f, th, s, z, sh.

💥 Plosive - a consonant produced by closing and then releasing the articulators somewhat forcefully. Think: b, p, d, t, g, k.

🌬️/💥 Obstruent - a fricative or a plosive. Obstruents are flexible in that they can be more easily voiced or voiceless than sonorants (nasals/approximants). Every voiceless letter you can possibly think of is most likely an obstruent.

📚 Linguistic grammar & structure:

✡️ Semitic - a language family spoken throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Triconsonantal roots are a common feature of this language family.

🔤 Triconsonantal root - a basis of Semitic languages in which a meaningful sequence of three consonants are modified by binyanim (vowels) to change their definition. In Farroshar, consonants act as root modifiers.

🏃 Agent noun - a person or thing that performs an action, like runner, pilot, or scientist.

🌍 Demonym (adj. demonymic) - a group of people, like German, Japanese, or Farroshar.

🔗 Genitive - a case of noun or pronoun that indicates association with or possession of. Think: John’s book, book of John, his, hers.

💬 Dialect (adj. dialectal) a version of a language that’s spoken in its own region.

✳️ Diacritic - a mark written above a letter to change the way it’s said, used in Farroshar to indicate vowels based on the number of diacritic dots and where they’re located.

🌱 Derivative - a term that comes from an older word or root.